by Alifair Skebe

October is American Cheese Month, begun annually since its inception last year through the American Cheese Society (ACS) and The State of Colorado. While the words “American Cheese” to many American readers may conjure up images of the ubiquitous solid yellow mass that turns into a gooey melty foodstuff, invented nearly one hundred years ago, this iconic symbol of American industrial food culture is not exactly what ACS means to promote. The larger category of American Cheese, including farmstead, artisan, cooperative, as well as industrially-produced natural cheeses is ACS’ prerogative. Like ACS, this month The Cheese Traveler will be celebrating our wide variety of delicious, award-winning, and spectacular small production American cheeses. Still, it’s hard to hear the words American Cheese Month and not indulge in thoughts of processed cheese synonymous with U.S. Patriotism and North American culture.

Adopted from Swiss technology and patented in the U.S. by Ontario-born James L. Kraft, so-called “American Cheese” caught the wave of the industrial revolution that promoted ease, efficiency, and economy in food production driven by the desire of both the producer and the consumer. Swiss food technicians Walter Gerber and Ted Kennel in 1911 discovered emulsifying salts’ and heat’s effect on coagulating naturally aged cheese to produce a new “product.”

This method derived from traditional fondue recipes that use additives such as beer and wine to keep the protein from separating from the oil during heating. Sodium phosphate, tartrate or citrate “help stabilize processed cheese by taking calcium from the milk protein and exchanging it with sodium. This allows the proteins to hold water, thickening the cheese” (Chapman). Cooked curd cheeses such as the German Kochkase and French Concoillotte may also be the conceptual origins of processed cheese for their meltable structure and additives in the ripening process. American Cheddar and Colby, also cooked curd cheeses, were the first cheeses to be used in processed “American Cheese” for their wide availability as well as their meltability.

Zey Ustunol, Professor of Food Science and Human Nutrition at MSU, remarks: “Processed cheese is made from natural cheeses that may vary in degree of sharpness of flavor. Natural cheeses are shredded and heated to a molten mass. The molten mass of protein, water and oil is emulsified during heating with suitable emulsifying salts to produce a stable oil-in-water emulsion. Depending on the desired end use, the melted mixture is then reformed and packaged into blocks, or as slices, or into tubs or jars. Processed cheeses typically cost less than natural cheeses; they have longer shelf-life, and provide for unlimited variety of products.”

Kraft, a savvy businessman,

James L. Kraft, food industry pioneer

immediately seized on the emerging technology and patented it in the U.S., foreseeing the possibilities for its advancement in and of food culture. Consequently, he secured military food contracts during WWI based on the product’s durability. Upon the soldiers’ return, men who developed a taste for the mild, slightly sweet and salty, standardized taste of the processed cheese found it easily obtainable in the emergent industrial processed food market. Most people at the time, did not have access to cold food storage and Kraft’s cheese did not need refrigeration and could be kept up to ten months, in both warm and cold climates. Processed cheese was more expensive than its predecessor; however, natural cheese was more perishable. It did not have a consistent shelf life and could neither withstand the heat of the southern and western climates, nor the difficulty of interstate shipment. Thus, the processed variety, “American Cheese,” began to unify the modern industrial nation.

On the other hand, traditionally-produced cheese has a long history in North America. Colonial settlers brought European and British cheesemaking traditions to the New World. U.S. cheeses developed in New England and migrated West, first following the Erie canal and its subsidiaries and then the railroad further westward, as cold storage methods improved cheese’s portability, into Ohio, Wisconsin, and beyond to Oregon and the Western seaboard. According to the National Historic Cheesemaking Center: “Puritan woman were the artisans of cheese during [the colonial] period…On the farm, it was almost always the role of women to make cheese and carry on the tradition.” Cheesemaking was a necessity to the settlers, thereby turning what would spoil into a stable product, given the right climatic conditions. The famous words of journalist and critic Clifton Fadiman characterize this economy: A cheese may disappoint. It may be dull, it may be naive, it may be oversophisticated. Yet it remains cheese, milk’s leap toward immortality.

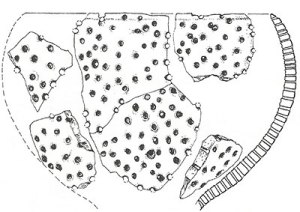

By early 1800, cheesemaking moved from New England to the Mohawk region of New York, where the first cheese factory was built, auspiciously in Rome, NY.

view of Rome, NY

As the farmstead U.S. cheese economy shifted to cooperative and industrial models, women’s role in cheesemaking subsided, paving the way for industrial progress and consumer demand. Following the cheesemaking methods developed in NY State factories, US cheese production focused on harder British style cheeses, which came to be known as “American Cheddar.” These cheeses were easier to produce on a large scale, fit well with the development of the industrial dairy model, and provided a more consistent and stable product for consumers. As cheesemaking spread to the Midwest, production of Colby (another British style) and Brick Cheese (Swiss/German style) became a widespread part of American cheesemaking tradition.

Kraft’s production of processed “American cheese” has always relied on the cheesemaking industry because Kraft uses the scraps and byproducts of naturally aged cheese as its foundation. Kraft’s process meted out the variations of the different refuse cheeses, some being mild and others quite sharp, by blending them through both heat and emulsification, thereby creating a very standardized product with little to no variation from one loaf to the next. In addition to its longevity, it had superior meltability, easily applicable to the emerging “fast food” business.

The Great Depression of the 1930s and WWII marked the test case for processed cheese. As women were drawn into the workforce, they needed fast, cheap meals. Kraft’s mac-n-cheese was one such answer. Marketed as a four person meal for 19 cents and a meal in under seven minutes that didn’t need a stove: “By 1930 over 40% of cheese consumed in the U.S. was Kraft’s — and that was in spite of its relatively high price. Thanks to clever advertising, Kraft was able to charge more in exchange for a promise of safety and consistency, even though the product was derived from inferior cheese” (Clark).

While industrially-produced foods and advertising took hold of a large segment of the American population, scarcity encouraged individual industry. Government programs promoted home canning and bringing back the lost art of home kitchen cheesemaking to housewives, such as the 1934 bulletin by the U.S. Department of Agriculture “An American-type Cheese…how to make it for home use.”  However, these efforts were eclipsed by the promotion of “American Cheese” through government military contracts provided to Kraft during WWII and subsequently to stabilize milk and cheese prices in the mid to late-twentieth century through government subsidy programs. At this time “American Cheese” became synonymous with “government cheese” offered free to the public and warehoused to offset prices. Sean McCloud, an associate professor of Religious Studies at UNC-Charlotte recalls: “[The Reagan era] was also a period when I ate my share of government cheese, packaged as two-pound blocks of uncut, white American, and distributed at Monon’s community center. We were not poor enough to be on welfare, but we were not so financially secure as to refuse government cheese.” Government endorsement by these means allowed for and promoted the dominance of processed cheese in food culture. Moreover, as consumer (and government) demand increased, Kraft began to dominate the cheese market buying up large producer contracts and effectively pushing small producers and factories, such as cooperatives, farmstead and artisan, out of business. In the later half of the 20th Century through producer and consumer insistence, the USDA developed industry standards and a four-category system for processed cheese, no longer allowing companies to call their processed products “Cheese” and enforcing labeling restrictions. Processed cheese is still promoted by the USDA and reinforced through government programs such as WIC (which only allows for the purchase of processed cheese) as a nutritious alternative to unprocessed varieties.

However, these efforts were eclipsed by the promotion of “American Cheese” through government military contracts provided to Kraft during WWII and subsequently to stabilize milk and cheese prices in the mid to late-twentieth century through government subsidy programs. At this time “American Cheese” became synonymous with “government cheese” offered free to the public and warehoused to offset prices. Sean McCloud, an associate professor of Religious Studies at UNC-Charlotte recalls: “[The Reagan era] was also a period when I ate my share of government cheese, packaged as two-pound blocks of uncut, white American, and distributed at Monon’s community center. We were not poor enough to be on welfare, but we were not so financially secure as to refuse government cheese.” Government endorsement by these means allowed for and promoted the dominance of processed cheese in food culture. Moreover, as consumer (and government) demand increased, Kraft began to dominate the cheese market buying up large producer contracts and effectively pushing small producers and factories, such as cooperatives, farmstead and artisan, out of business. In the later half of the 20th Century through producer and consumer insistence, the USDA developed industry standards and a four-category system for processed cheese, no longer allowing companies to call their processed products “Cheese” and enforcing labeling restrictions. Processed cheese is still promoted by the USDA and reinforced through government programs such as WIC (which only allows for the purchase of processed cheese) as a nutritious alternative to unprocessed varieties.

Since the close of the Reagan-era, the U.S. has seen a resurgence in farmstead and artisan cheesemakers. While American Cheese remains a recognizable comfort food, consumer taste has begun to shift away from standardized and stable industrial cheeses. Consumers also express growing concerns over the additives in processed cheese. Several do-it-yourself guides teach home cooks how to make their own processed cheese so you will “know exactly what went into it” (Ruperti). This is occurring at the same time the Slow Food and Local and Region Food movements have profoundly encouraged interest in small cheese producers across the nation.

The American Cheese Society promotes the cheesemaking industry on a variety of levels from the consumer to the cheesemaker to the retailer. Moreover, ACS promotes continued development of American cheeses from old world traditions to newer ones through education and yearly awards at its annual conference and American cheese competition. The Cheese Traveler stands with ACS in promoting a diverse image of American Cheese and supporting small cheesemakers. This month we will celebrate the great taste and craftsmanship of American cheese. Watch for our meet the cheesemaker demos and promotions that feature our great American cheese selection.

from “The Stellar American-Made Cheese Plate,” J.J. Goode, May 2010, Details.com

Sources:

“Brief History of Cheese.” National Historic Cheesemaking Center. Monroe, WI. 2009

Chapman, Sasha. “Manufacturing Taste: The (un)natural history of Kraft Dinner—a dish that has shaped not only what we eat, but also who we are.” The Walrus. Sept 2012

Clark, David. “A Brief History of “American Cheese,” from Colonial Cheddar to Kraft Singles” Mental_Floss. Jan. 7, 2009

Durand Jr., Loyal. “The Migration of Cheese Manufacture in the United States.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 42.4 (Dec 1952): 263-282.

McCloud, Sean. “Indiana: A Hoosier Remembers Eating Government Cheese.” Religion and Politics: The States Project. Washington University, St. Louis. August 22, 2012.

Ruperti, Yvonne. “How to Make American Cheese.” America’s Taste Kitchen Feed: Do-It-Yourself. Sept. 2011.

Urban, Shilo. “American Cheese: Neither American Nor Cheese.” Organic Authority. 2010.

Ustunol, Zey. “ Processed Cheese: What Is That Stuff Anyway?” Michigan Dairy Review. 14.2 (April 2009).

Walter, H. E.. An American-type cheese : how to make it for home use.. Washington, D.C.. UNT Digital Library.