Cheese Making Simplified

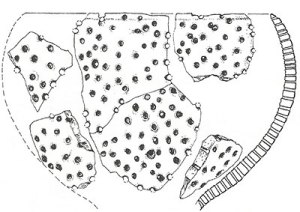

Cheese making is at least 7500 years old according to our current archeological records. Ancient pottery shards from cheese strainers containing cheese cultures were recently found in ancient sites in Poland and China.

Ripening the Milk

Cheese production begins with milk from four animals: cow, sheep, goat, and water buffalo. The milk is poured into a vat for pasteurization or thermalization and heated before adding a starter culture. For raw milk cheeses, a starter culture is added directly to the vat without heating the milk. The milk is then given a few minutes to an hour to begin acid production before adding rennet to begin the coagulating process.

Cutting the Curd

After curds begin to form, they are cut with stretched steel blades that resemble a large comb. Cutting the curd must be done at just the right time so as not to loosen any fine curds necessary in curing the cheese.

Removing the Whey

Most cheeses require straining to remove whey. Some cheeses, such as Gruyere, are cooked in their whey before straining. The combination of heat and increasing acidity aids in syneresis, or the expulsion of moisture from the proteins in the curd. Cheddar curds are stirred and folded in a process known as cheddaring, which minimally heats the curds and allows them to knit together while simultaneously expelling whey.

Washing the Curd

After straining, some cheeses are washed with a water bath that removes any lingering whey and lactose. Adding water to the curd produces a very moist cheese like Muenster or Brick. Gouda is washed in hot water, which helps to dry the curd and create its characteristic texture.

This Medieval woodcut shows many uses for milk and cream. The center fromager is washing and straining the curd to make cheese; peasant churns cream into butter; large wheels of cheese age on shelves in the background.

Handling the Curd

Many cheeses that are brined or surface salted are collected into molds or pressed directly under the whey. Blue cheese, for example, is pressed into a hoop, salted, and left for a week before perforating its edges to allow air inside. Gouda and Swiss are pressed under whey, which encourages a smooth texture and prevents escape of air in the aging process. Cheeses such as Cheddar and Pasta Filata (mozzarella) are kept warm in a vat to ferment before salting. Pasta Filata cheeses are then worked and stretched in the warm water before curing.

Pressing the Curd

Curds are collected and then pressed into molds such as baskets, crocks, wooden hoops or metal cylinders. Soft cheeses require almost no pressure while some varieties require up to 25 pounds of pressure per square inch to form. Generally, the warmer the curd, the less pressure required, which may be another reason for cooking the curd of those 75 lb. wheels of Alpine cheese!

Salting the Curd

Adding salt is important for many reasons. It encourages improvement of curds, slows acid development, helps prevent spoilage, and controls ripening and flavor. Salting cheese follows three techniques: adding salt to the curd before pressing such as Cheddar, surface salting after pressing, and brine salting. Brine salting or washing the surface of the cheese (also known as smear-ripening) can occur once or continue periodically throughout the aging process.

Curing the Cheese

Cheeses range from un-aged, “fresh” cheeses to young cheeses that can be aged from two weeks up to two months to aged cheeses that can be aged from three months to many years. Nascent cheeses are placed in modern humidity-controlled “caves” that imitate the original cave environments of traditional cheeses. Cheeses such as Brie and Camembert are meant to be enjoyed under two months of age, as the aging process will spoil the surface cultures of the cheese. Other cheeses, like a fine wine, become more enjoyable with age as their texture and flavor intensify through the aging process.